TUPLE UNPACKING CODE

(This code could throw a memory error if the source file is exceptionally large, but that’s the least of our problems.) filename ) as srcfile : lines = list ( itertools. extract_stack () # Read all the lines up to the point where ``Trues2()`` is Import itertools def Trues2 (): # Find the line where this function is calledĬurrent_frame = traceback. If you’ve used Python for any length of time, you’ve probably seen an example of reflection-like behaviour, even if you didn’t realise it. We could jump straight to the end, but let’s go through all of them in turn to see how I tried to tackle the problem. This is a technique called reflection, where a program can read or modify its own source code.Īnything involving reflection and parsing source code is prone to be fiddly, so I actually wrote four implementations, each less buggy than the last. To make this work, such a function needs to be able to see the source code where it’s being called. So this boils down to the following question: how can a function know the length of the tuple it’s being unpacked into? The only way this can work is if Trues can dynamically resize itself to be the correct length.

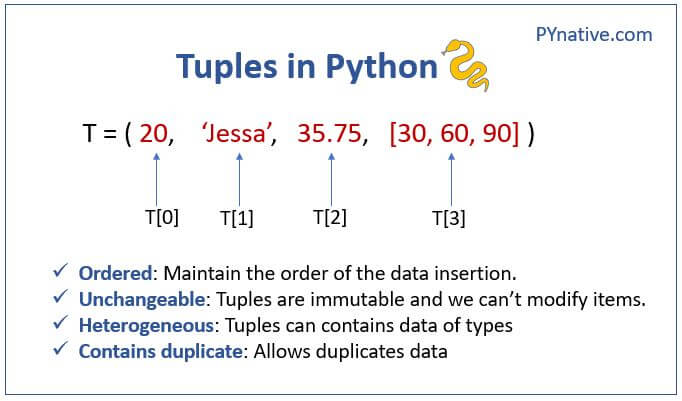

This means that Trues has to return the same number of elements as there are variables on the left-hand side – in this example, four – and the number of variables can vary. Remember that tuple unpacking only works if you have the same number of elements on both sides. It wasn’t until the evening, when I was on my daily walk, that gears began to turn in my brain and I thought about how you might actually do this. We all had a laugh, briefly discussed what dark magic it might take to pull this off, and then conversation moved on. Kathy: You should be able to use that as tuple unpacking Here’s a conversation from a group chat last week (shared with permission): The details of tuple unpacking could be a whole other blog post here it’s sufficient to know that this feature exists and you need to balance both sides for it to work. ValueError: too many values to unpack (expected 3) For example: > longitude, latitude, altitude = 51.9, -0.2 The structures longitude, latitude and 51.9, -0.2 are both Python tuples – the parentheses you often write around tuples are optional.įor tuple unpacking to work, you need to have the same number of variables on the left-hand side as elements on the right, so they can be paired up together.

Many programming languages support parallel assignment, which allows you to set multiple variables at once:ĭef get_position (): return 51.9, - 0.2 longitude, latitude = get_position ()Īnother name for this is tuple unpacking. Image by Kristopha Hohn on Flickr, used under CC BY-SA. Sensibility says overusing reflection will bring seven years of filthy looks from everybody who has to maintain your code. Superstition says breaking a mirror will bring seven years of bad luck. You can skip to the end if you just want the practical lessons. You might find it interesting anyway, but this is probably more niche than my posts. That said, even bad ideas can have interesting things to tell us, so in this post I’m going to explain how it works and how I wrote it.Īttention conservation notice: I had fun trying this idea, and writing out the notes was a useful exercise, but I don’t know how much other people will get out of it. It needs reflection and the exec() function to work, and should never be used for anything serious. Making that tweet work requires a horrific misuse of tuple unpacking, a feature that is usually used for sensible things.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)